|

Today’s news is also likely to further erode whatever remaining trust Brazilians feel for their country’s political elite. In a recent survey by Ipsos, 94 percent of Brazilians said they don’t feel represented by their politicians. José Maria de Souza Junior, an international relations professor at Rio Branco University in Sao Paulo, said Brazilians are facing a moral crisis. “When the economy is doing badly, when there are no jobs, we respond to that … We are very sensitive,” he said.

In recent years, as crisis has consumed Brazil, there has been a notable shift in political, social, and religious attitudes. According to a 2016 survey, 54 percent of the Brazilian population held a high number of traditionally-conservative opinions, up from 49 percent in 2010. The shift is particularly evident on matters of law and order: Today, more Brazilians are in favor of legalizing capital punishment, lowering the age at which juveniles can be tried as adults, and life without parole for individuals who commit heinous crimes. Observers have ascribed this phenomenon to Brazilians’ increasing fear of violence over the last few years. This rightward shift has been accompanied by a massive growth in the country’s Evangelical Protestant and Pentecostal churches, which constitute the greater part of Brazilian Protestantism. The percentage of those who identified as evangelicals in Brazil has grown from 6.6 percent in 1980, to 22.2 percent in 2010.

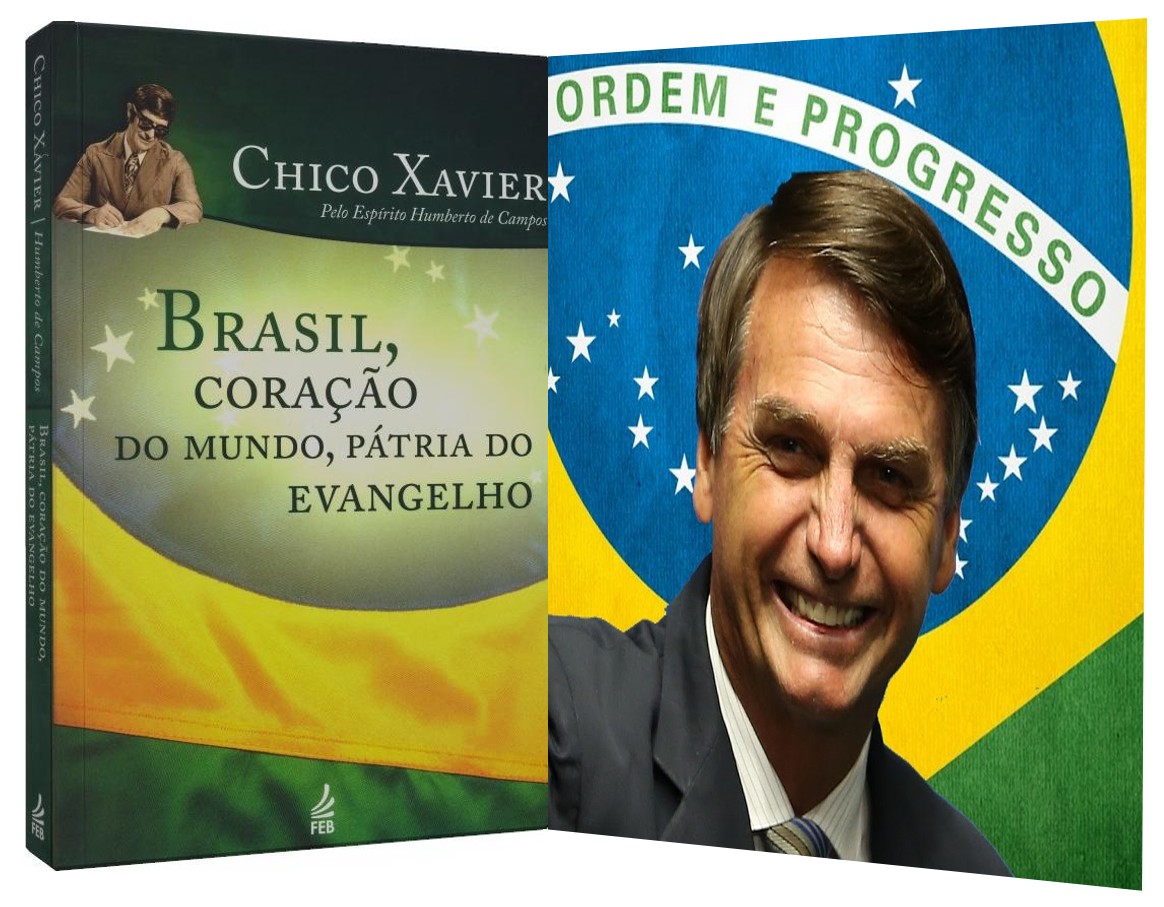

Perhaps the clearest articulation of this shift has been the rise of 62-year old military officer-turned-congressman Jair Messias Bolsonaro. In a time when corruption has tarnished Brazil’s political class, his blunt charisma, zeal for law and order, and rapport with Brazil’s evangelicals, have turned what would ordinarily be glaring weaknesses into strengths. He has defended the legalization of capital punishment, and argued that the “politics” of “human rights, and of the politically correct, give space to those who are against the law and on the side of criminals.” He has said he’d rather have “a dead son over a gay son” and that he would not rape a particular female deputy in congress because “she wasn’t worthy of it.” Political parties, congressmen, and even the Brazilian Bar Association, have filed a total of 30 requests to have him removed from his position as federal deputy for the city of Rio de Janeiro, a position he’s occupied for nearly three decades, for actions that broke congressional decorum, like sending death threats to another member of Congress and saying the military regime that ruled Brazil for 30 years “should have killed more people.” He has shown no particular grasp of policy: When questioned about how he was planning on ensuring a fiscal surplus, keeping inflation low, and maintaining a floating exchange rate (known as Brazil’s macroeconomic tripod, which has been the basis of economy policy in the country since 1999), he said that the person who needed to understand such things would be his finance minister, who he’d appoint if elected.

Despite Bolsonaro’s considerable baggage, as of last December, 21 percent of Brazilians said they would vote for him for president in this year’s election should he choose to run. While that’s not enough to get him through the primaries, his rising popularity suggests a transformation in Brazilian society that may be picking up speed.

loading...

No comments:

Post a Comment